1. Introduction

Ethereum is becoming a popular altnative coin of Bitcoin. Ethereum implements blockchain in a generalised manner. Furthermore it provides a plurality of resources, each with a distinct state and operating code but able to interact through a message-passing framework with others. The smart contract scheme allows users to customise transaction procedures and enable blockchain of sophisticated business logics. In this post, we will talk about the data structures and its extensions from Bitcoin.

2. Bitcoin As A State Transition System

From a technical standpoint, the Bitcoin ledger can be thought of as a state transition system, where there is a “state” consisting of the ownership status of all existing bitcoins and a “state transition function” that takes a state and a transaction and outputs a new state which is the result. Here is the fomulation:

For example:

The “state” in Bitcoin is the collection of all coins (technically, “unspent transaction outputs” or UTXO) that have been minted and not yet spent, with each UTXO having a denomination and an owner. A transaction contains one or more inputs, with each input containing a reference to an existing UTXO and a cryptographic signature produced by the private key associated with the owner’s address, and one or more outputs, with each output containing a new UTXO to be added to the state.

The state transition function APPLY(S,TX) > S’ can be defined roughly as follows:

- For each input in TX: i. If the referenced UTXO is not in S, return an error. ii. If the provided signature does not match the owner of the UTXO, return an error.

- If the sum of the denominations of all input UTXO is less than the sum of the denominations of all output UTXO, return an error.

- Return S with all input UTXO removed and all output UTXO added.

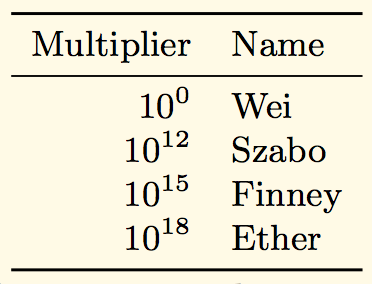

3. Currency unit of Ethereum

Ethereum has an intrinsic currency, Ether, known also as ETH. The smallest subdenomination of Ether, and thus the one in which all integer values of the currency are counted, is the Wei. One Ether is defined as being 1018 Wei. Here is a summarised list of units:

4. Ethereum Blocks, State and Transactions

4.1 World States

The world state (state), is a mapping between addresses (160-bit identifiers) and account states. The account state comprises the following four fields:

-

nonce: A scalar value equal to the number of transactions sent from this address or, in the case of accounts with associated code, the number of contract-creations made by this account.

-

balance: A scalar value equal to the number of Wei owned by this address.

-

storageRoot: A 256-bit hash of the root node of a Merkle Patricia tree that encodes the storage contents of the account (a mapping between 256-bit integer values), encoded into the trie as a mapping from the Keccak 256-bit hash of the 256-bit integer keys to the RLP-encoded 256-bit integer values.

-

codeHash: The hash of the EVM code of this account—this is the code that gets executed should this address receive a message call; it is immutable and thus, unlike all other fields, cannot be changed after construction. All such code fragments are contained in the state database under their corresponding hashes for later retrieval.

4.2 Transactions

There are two types of transactions: those which result in message calls and those which result in the creation of new accounts with associated code (known informally as ‘contract creation’). Both types specify a number of common fields:

-

nonce: A scalar value equal to the number of transactions sent by the sender.

-

gasPrice: A scalar value equal to the number of Wei to be paid per unit of gas for all computation costs incurred as a result of the execution of this transaction.

-

gasLimit: A scalar value equal to the maximum amount of gas that should be used in executing this transaction. This is paid up-front, before any computation is done and may not be increased later.

-

to: The 160-bit address of the message call’s recipient or, for a contract creation transaction, the to is 0.

-

value: A scalar value equal to the number of Wei to be transferred to the message call’s recipient or, in the case of contract creation, as an endowment to the newly created account.

-

v, r, s: Values corresponding to the signature of the transaction and used to determine the sender of the transaction.

Additionally, a contract creation transaction contains: init: An unlimited size byte array specifying the EVM-code for the account initialisation procedure.

In contrast, a message call transaction contains: data: An unlimited size byte array specifying the input data of the message call.

4.3 Blocks

The block in Ethereum is the collection of relevant pieces of information (known as the block header), H, together with information corresponding to the comprised transactions, T, and a set of other block headers U that are known to have a parent equal to the present block’s parent’s parent (such blocks are known as ommers). The block header contains several pieces of information:

-

parentHash: The Keccak 256-bit hash of the parent block’s header, in its entirety.

-

ommersHash: The Keccak 256-bit hash of the ommers list portion of this block.

-

beneficiary: The 160-bit address to which all fees collected from the successful mining of this block be transferred.

-

stateRoot: The Keccak 256-bit hash of the root node of the state trie, after all transactions are executed and finalisations applied.

-

transactionsRoot: The Keccak 256-bit hash of the root node of the trie structure populated with each transaction in the transactions list portion of the block.

-

receiptsRoot: The Keccak 256-bit hash of the root node of the trie structure populated with the receipts of each transaction in the transactions list portion of the block.

-

logsBloom: The Bloom filter composed from indexable information (logger address and log topics) contained in each log entry from the receipt of each transaction in the transactions list.

-

difficulty: A scalar value corresponding to the difficulty level of this block. This can be calculated from the previous block’s difficulty level and the timestamp.

-

number: A scalar value equal to the number of ancestor blocks. The genesis block has a number of zero.

-

gasLimit: A scalar value equal to the current limit of gas expenditure per block.

-

gasUsed: A scalar value equal to the total gas used in transactions in this block.

-

timestamp: A scalar value equal to the reasonable output of Unix’s time() at this block’s inception.

-

extraData: An arbitrary byte array containing data relevant to this block. This must be 32 bytes or fewer.

-

mixHash: A 256-bit hash which proves combined with the nonce that a sufficient amount of computation has been carried out on this block.

-

nonce: A 64-bit hash which proves combined with the mix-hash that a sufficient amount of computation has been carried out on this block.

5. Gas and Payment

In order to avoid issues of network abuse and to sidestep the inevitable questions stemming from Turing completeness, all programmable computation in Ethereum is subject to fees. The fee schedule is specified in units of gas. Thus any given fragment of programmable computation (this includes creating contracts, making message calls, utilising and accessing account storage and executing operations on the virtual machine) has a universally agreed cost in terms of gas.

Every transaction has a specific amount of gas associated with it: gasLimit. This is the amount of gas which is implicitly purchased from the sender’s account balance. The purchase happens at the according gasPrice, also specified in the transaction. The transaction is considered invalid if the account balance cannot support such a purchase. It is named gasLimit since any unused gas at the end of the transaction is refunded (at the same rate of purchase) to the sender’s account. Gas does not exist outside of the execution of a transaction. Thus for accounts with trusted code associated, a relatively high gas limit may be set and left alone.

In general, Ether used to purchase gas that is not refunded is delivered to the beneficiary address, the address of an account typically under the control of the miner. Transactors are free to specify any gasPrice that they wish, however miners are free to ignore transactions as they choose. A higher gas price on a transaction will therefore cost the sender more in terms of Ether and deliver a greater value to the miner and thus will more likely be selected for inclusion by more miners. Miners, in general, will choose to advertise the minimum gas price for which they will execute transactions and transactors will be free to canvas these prices in determining what gas price to offer. Since there will be a (weighted) distribution of minimum acceptable gas prices, transactors will necessarily have a trade-off to make between lowering the gas price and maximising the chance that their transaction will be mined in a timely manner.

6. Execution Model

The EVM is a simple stack-based architecture. The word size of the machine (and thus size of stack item) is 256-bit. This was chosen to facilitate the Keccak-256 hash scheme and elliptic-curve computations. The memory model is a simple word-addressed byte array. The stack has a maximum size of 1024. The machine also has an independent storage model; this is similar in concept to the memory but rather than a byte array, it is a wordaddressable word array. Unlike memory, which is volatile, storage is non volatile and is maintained as part of the system state. All locations in both storage and memory are well-defined initially as zero. The machine does not follow the standard von Neumann architecture. Rather than storing program code in generally-accessible memory or storage, it is stored separately in a virtual ROM interactable only through a specialised instruction.

7. Final remarks

This post introduces the data structures and extensions of Ethereum. In next post, we will talk about how to program smart contract with Ethereum.