1. Introduction

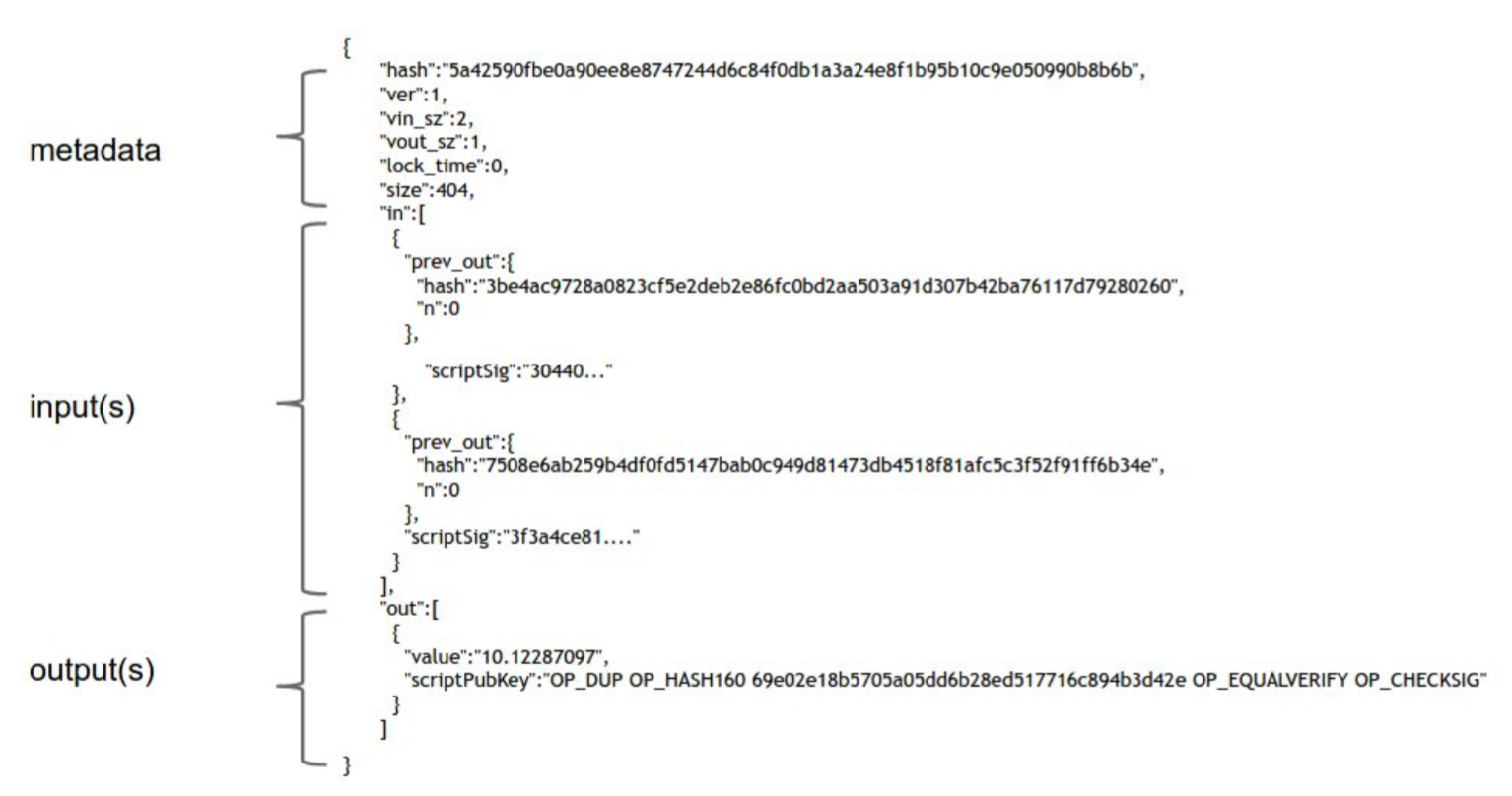

In this post, we will look at real data structures of blocks and transactions, real scripts Bitcoin use. Let’s start with transaction structures. The figure below shows the data structure of a transaction.

To view the real transactions happening in Bitcoin network, some websites can be referred to such as blockchain.info. As we can see from the figure, there are three parts to a transaction: some metadata, a series of inputs, and a series of outputs.

To view the real transactions happening in Bitcoin network, some websites can be referred to such as blockchain.info. As we can see from the figure, there are three parts to a transaction: some metadata, a series of inputs, and a series of outputs.

-

Metadata. There’s some housekeeping information — the size of the transaction, the number of inputs, and the number of outputs. There’s the hash of the entire transaction which serves as a unique ID for the transaction. That’s what allows us to use hash pointers to reference transactions. Finally there’s a “lock_time” field. The way it works is that if you specify any value other than zero for the lock time, it tells miners not to publish the transaction until the specified lock time. The transaction will be invalid before either a specific block number, or a specific point in time, based on the timestamps that are put into blocks. So this is a way of preparing a transaction that can only be spent in the future if it isn’t already spent by then.

-

Inputs. The transaction inputs form an array, and each input has the same form. An input specifies a previous transaction, so it contains a hash of that transaction, which acts as a hash pointer to it. The input also contains the index of the previous transaction’s outputs that’s being claimed. And then there’s a signature script: scriptSig which we will talk about it later. Remember that we have to sign to show that we actually have the ability to claim those previous transaction outputs.

-

Outputs. The outputs are again an array. Each output has just two fields. They each have a value, and the sum of all the output values has to be less than or equal to the sum of all the input values. If the sum of the output values is less than the sum of the input values, the difference is a transaction fee to the miner who publishes this transaction. The other field is scriptPubKey script.

2. Bitcoin Scripts

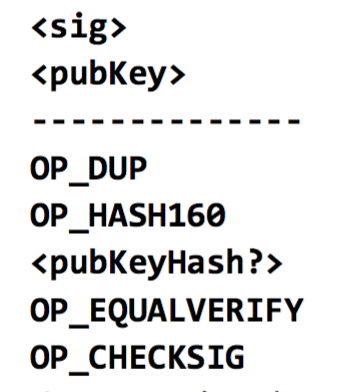

In this section, we will talk about the two scripts: scriptSig and scriptPubKey.

The most common type of transaction in Bitcoin is to redeem a previous transaction output by signing with the correct key. In this case, we want the transaction output to say, “this can be redeemed by a signature from the owner of address X.” An address is a hash of a public key. So merely specifying the address X doesn’t tell us what the public key is, and doesn’t give us a way to check the signature. So instead the transaction output must say “this can be redeemed by a public key that hashes to X, along with a signature from the owner of that public key.”

We concatenate the two scripts, and the resulting script must run successfully in order for the transaction to be valid. In the simplest case, the scriptPubKey just specifies a public key (or an address to which the public key hashes), and scriptSig specifies a signature with that public key.

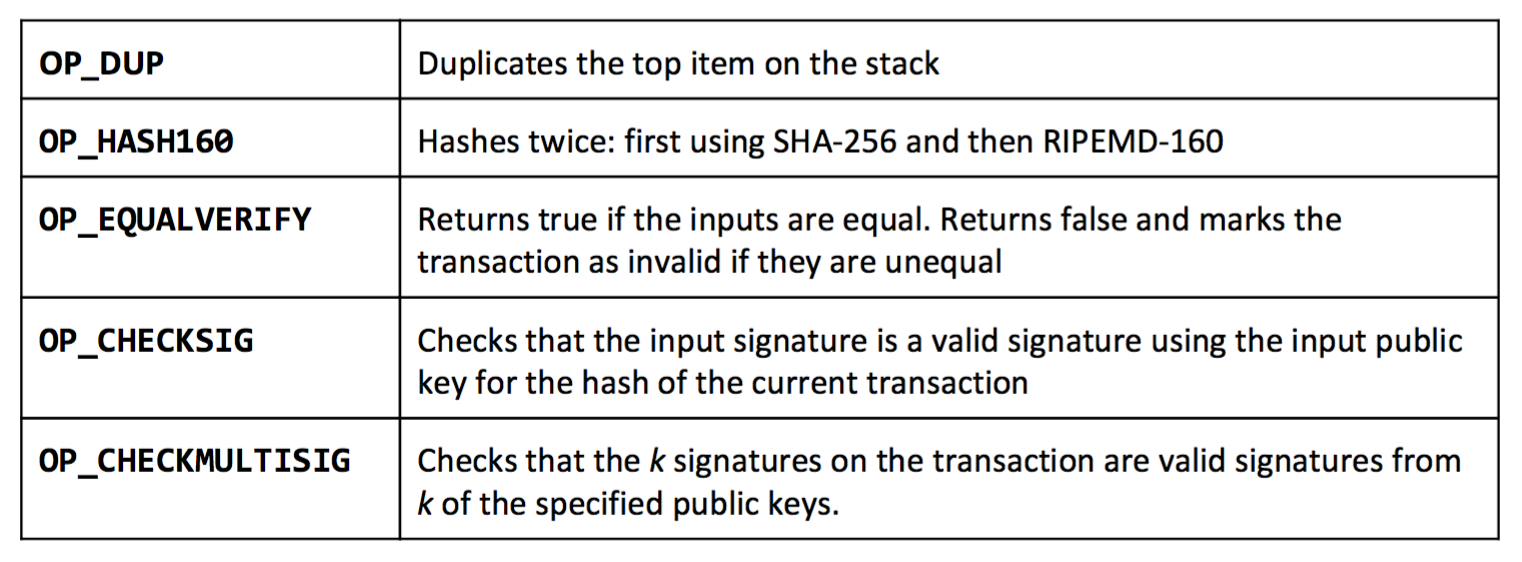

An example of combined script is shown above. The first part is scriptSig and the second part is scriptPubKey. The script is a stack based language and it does not have loop in it. Thus, we just need to run it line by line to check its validity. There are only two possible outcomes when a Bitcoin script is executed. It either executes successfully with no errors, in which case the transaction is valid. Or, if there’s any error while the script is executing, the whole transaction will be invalid and shouldn’t be accepted into the block chain. Some commonly used commands are shown below:

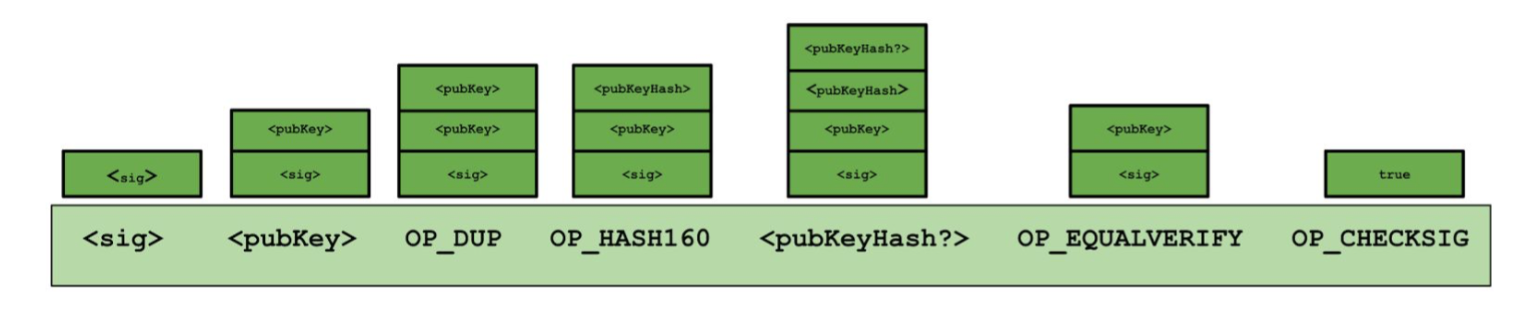

To execute a script in a stack-based programming language, all we’ll need is a stack that we can push data to and pop data from. The figure below illustrates what happens to the stack after each operation:

The Bitcoin scripting language is very small. There’s only room for 256 instructions, because each one is represented by one byte. Of those 256, 15 are currently disabled, and 75 are reserved. The reserved instruction codes haven’t been assigned any specific meaning yet, but might be instructions that are added later in time. Although this stack based language is not Turing-complete, it still makes Bitcoin more programmable and flexible. It has many applications such green address, escrow transactions, smart contract…

3. Block Structure

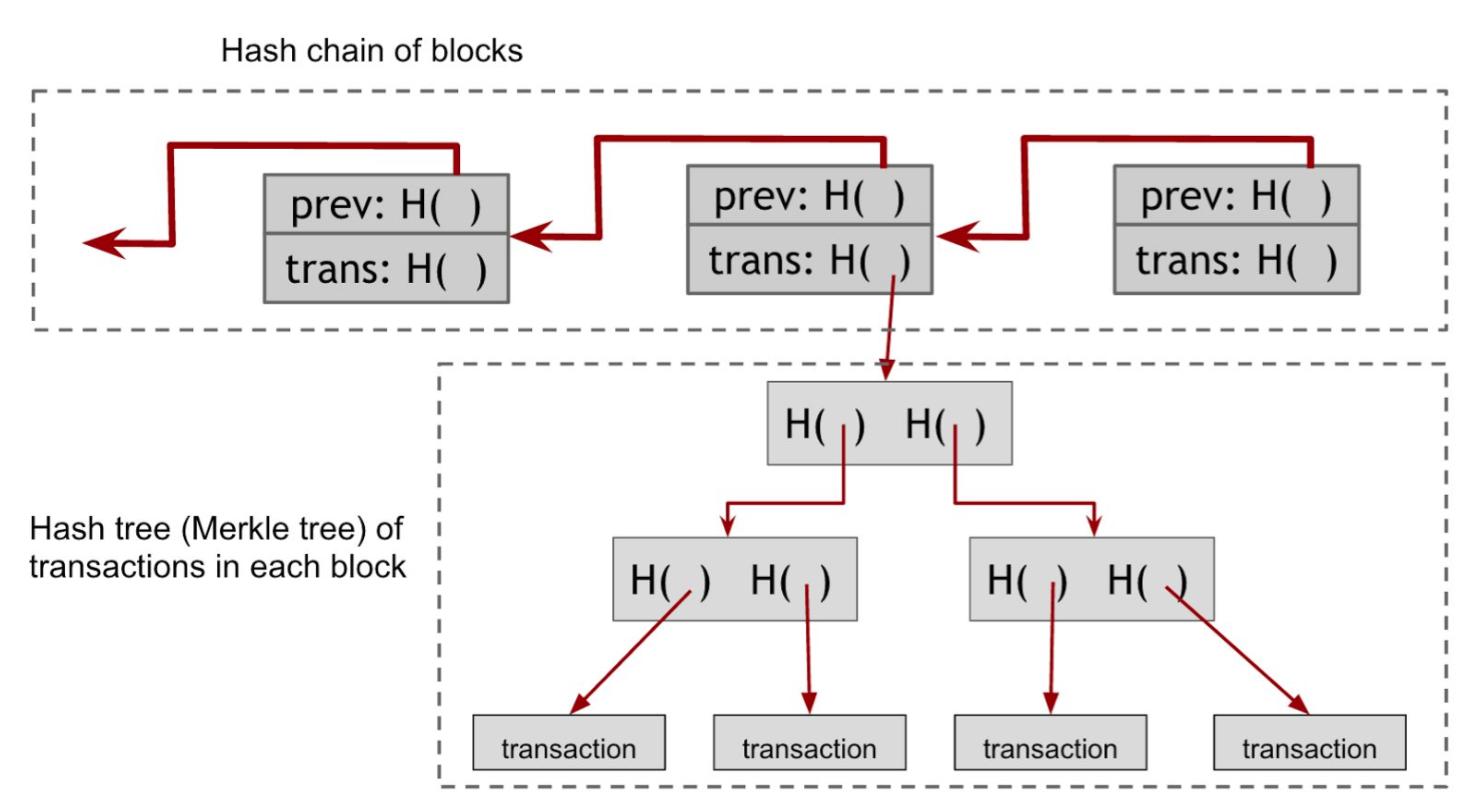

The block chain is a clever combination of two different hash-based data structures. The first is a hash chain of blocks. Each block has a block header, a hash pointer to some transaction data, and a hash pointer to the previous block in the sequence. The second data structure is a per-block tree of all of the transactions that are included in that block. This is a Merkle tree and allows us to have a digest of all the transactions in the block in an efficient way. The figure below shows an example:

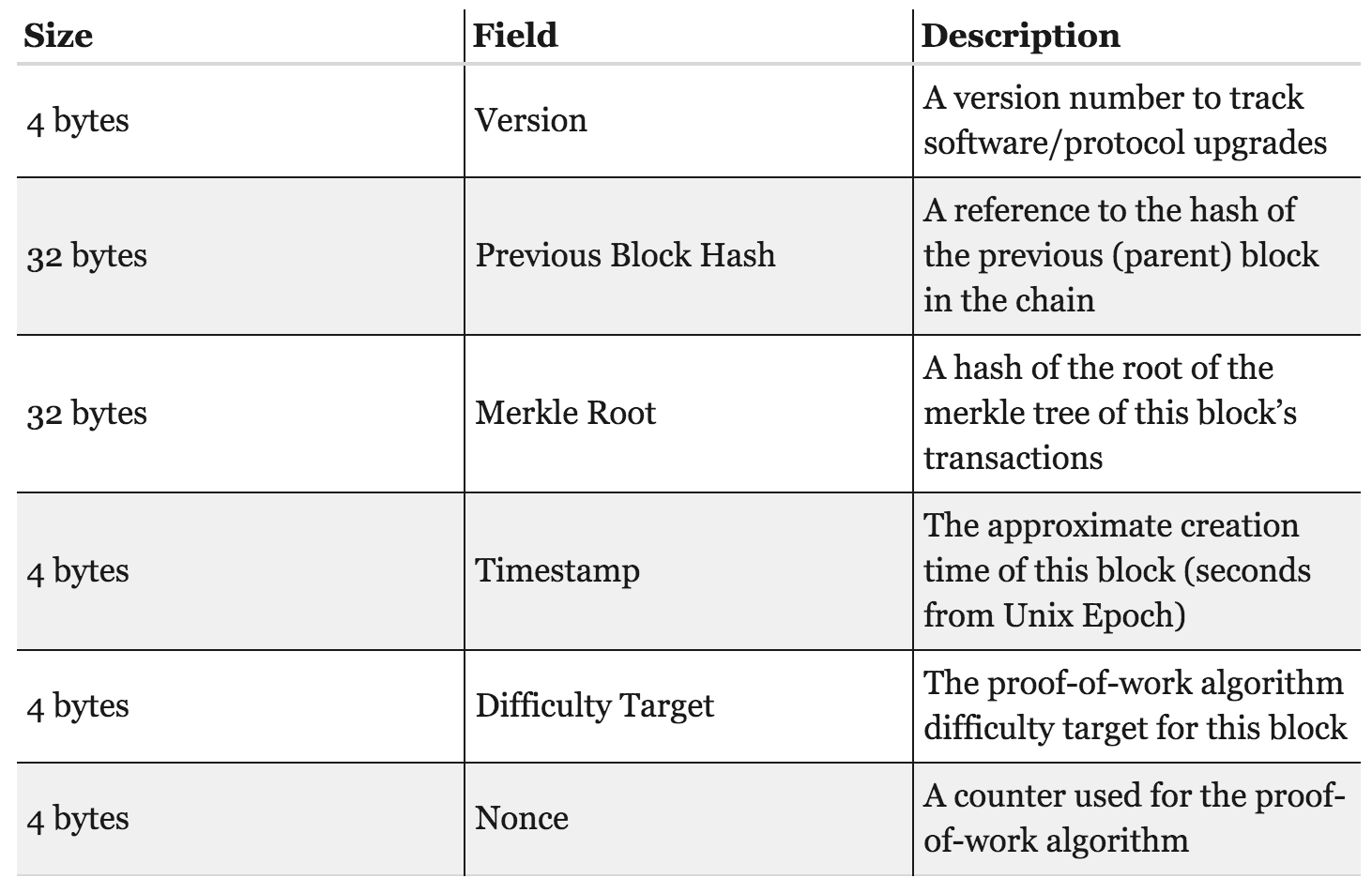

A block in block chain mainly has a header and a list of transactions. The format of the header is shown below:

The transactions are accumulated in 10 minutes and put into one block for efficiency reasons. There is a special type of transaction called coinbase which is the transaction that generates new Bitcoins. It mostly looks like a normal transaction but with several differences: (1) it always has a single input and a single output, (2) the input doesn’t redeem a previous output and thus contains a null hash pointer, since it is minting new bitcoins and not spending existing coins, (3) the value of the output is currently a little over 25 Bitcoins. The output value is the miner’s revenue from the block. It consists of two components: a flat mining reward, which is set by the system and which halves every 210,000 blocks (about 4 years), and the transaction fees collected from every transaction included in the block. (4) There is a special “coinbase” parameter, which is completely arbitrary — miners can put whatever they want in there.

4. Final remarks

This post introduces how the data structures of Bitcoin transactions and blocks. In next post, we will talk about the security and applications of Blockchain.