1. Introduction

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer digital asset and a payment system. The system is invented by Satoshi Nakamoto and released as an open-source software in 2009.

Bitcoins are created as a reward for payment processing work in which users offer their computing power to verify and record payments into a public ledger. This activity is called mining and miners are rewarded with transaction fees and newly created bitcoins. Besides being obtained by mining, bitcoins can be exchanged for other currencies, products, and services.

Bitcoin is revolutionising they way people pay and exchange products. In former days, currency is created and exchanged based on trusted institutions. The central bank issues currency and people make their payments via various ways such as commercial bank, PayPal, Alipay, Apple Wallet, etc. This centralised scheme has its own problems like counterfeit. On the contrary, In bitcoin system, transactions take place between users directly, without an intermediary. These transactions are verified by network nodes and recorded in a public distributed ledger called the blockchain.

This blog series is based on some excellent books and tutorials such as Master Bitcoin and Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies. The official documentation of bitcoin is also very helpful.

In the first post, we give some introduction on data structures and cryptography concepts used in blockchain and bitcoin.

2. Cryptographic Hash function

2.1 Properties

Cryptographic Hash function is used often in blockchain. For a hash function, it takes variable length input x and map it to a fixed size output H(x) (e.g. 256 bits for MD5 and SHA-256). A hash function must have three properties to become a cryptographic hash function:

-

Collision-resistance: A hash function H is said to be collision resistant if it is infeasible to find two values, x and y , such that x != y , yet H(x)= H(y).

-

Hiding: A hash function H is hiding if: when a secret value r is chosen from a probability distribution that has high entropy, then given H(r ‖ x) it is infeasible to find x. ‖ means concatenation of two strings.

-

Puzzle friendliness. A hash function H is said to be puzzle-friendly if for every possible n-bit output value y , if k is chosen from a distribution with high entropy, then it is infeasible to find x such that H(k ‖ x) = y in time significantly less than 2n.

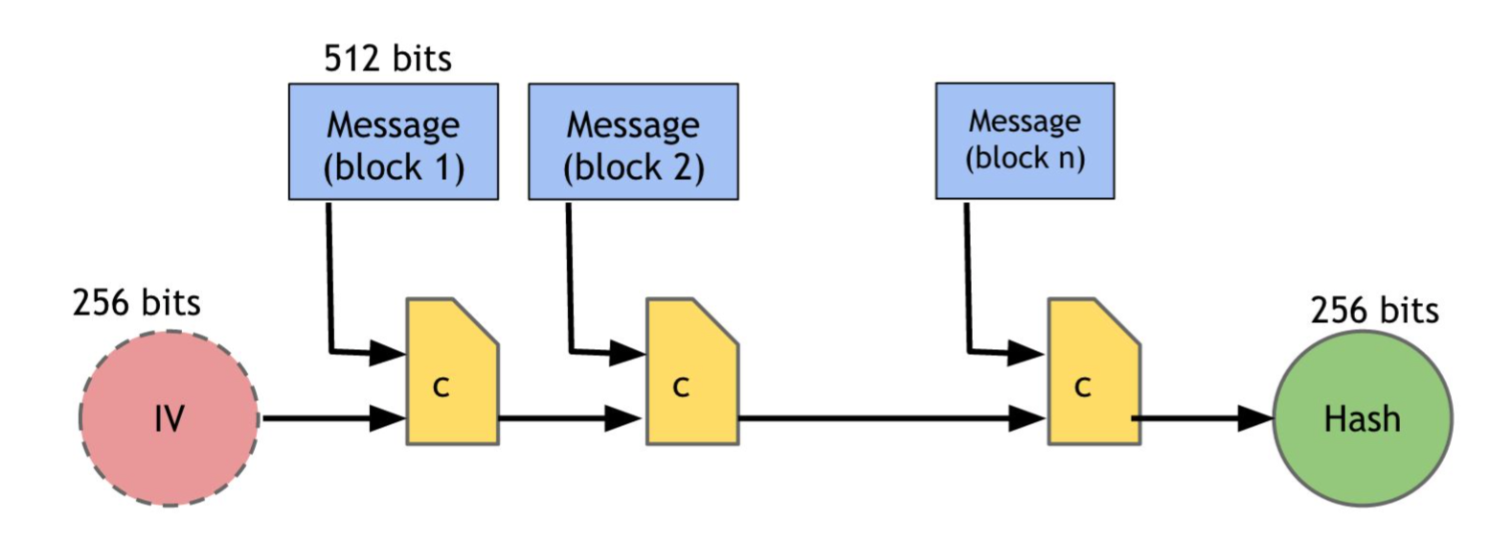

Given three properties, those hash functions can have a lot of practical applications. Hiding and puzzle friendliness guaranttee that it is infeasible to reverse-engineer intput x given hash value H(x). In Blockchain system, SHA-256 is the hardcore of the system. Given a data block, SHA-256 maps the data block to 256 bits. According to collision-resistance, since it is infeasible to find two different values that are mapped to the same hash value, we can safely use the 256 bits as the ID of the data block. SHA-256 is generated by a procedure called Merkle-Damgard transform. The procedure is shown below:

2.2 Hash Pointers

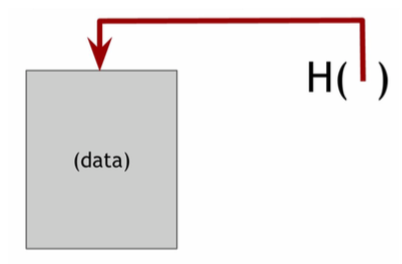

A hash pointer is simply a pointer to where some information is stored together with a cryptographic hash of the information. Whereas a regular pointer gives you a way to retrieve the information, a hash pointer also gives you a way to verify that the information hasn’t changed. In regular pointer such as in C/C++, the pointer stores the variable address. In a hash pointer, it simply stores the hash value H(x) of the data x it points to. An example is shown below.

In practice, the hash pointers can be indexed by database or structures like hash table to support efficient retrieval. Given hash pointers, we can use it to build all kinds of data structures. Intuitively, we can take a familiar data structure that uses pointers such as a linked list or a binary search tree and implement it with hash pointers, instead of pointers as we normally would. Here is two examples on blockchain and merkle tree.

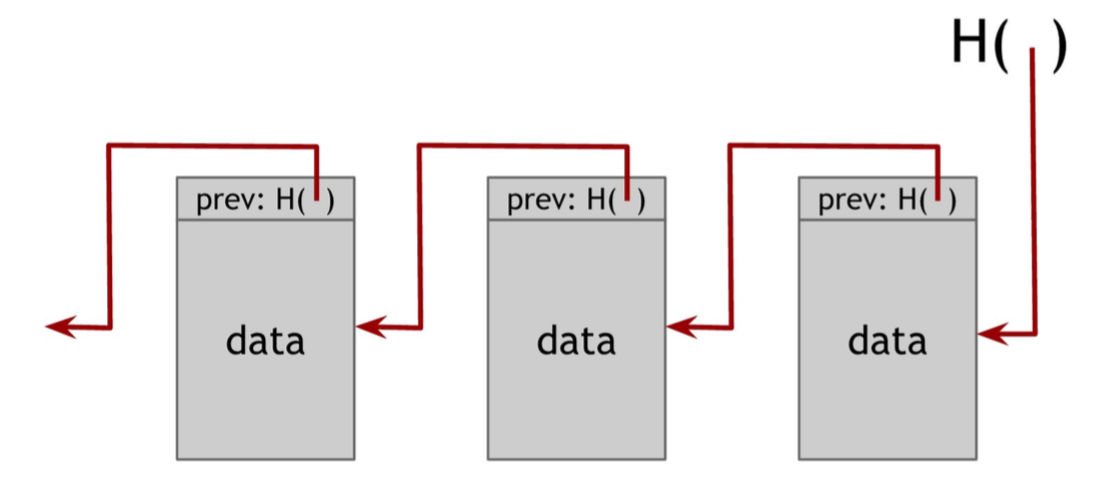

2.2.1 Blockchain

Blockchain is just a linked list using hash pointers. Whereas as in a regular linked list where you have a series of blocks, each block has data as well as a pointer to the previous block in the list, in a block chain the previous block pointer will be replaced with a hash pointer. So each block not only tells us where the value of the previous block was, but it also contains a digest of that value that allows us to verify that the value hasn’t changed. We store the head of the list, which is just a regular hash-pointer that points to the most recent data block.

This structures have the property that it is a tamper-evident log, i.e., if the attacher changes the data in the middle, he has to continue changing the hash pointers until the root of the blockchain. In a distributed environment, if others store a copy of the root of the blockchain, it can easily detect the blockchain in the attacker’s machine has been tampered.

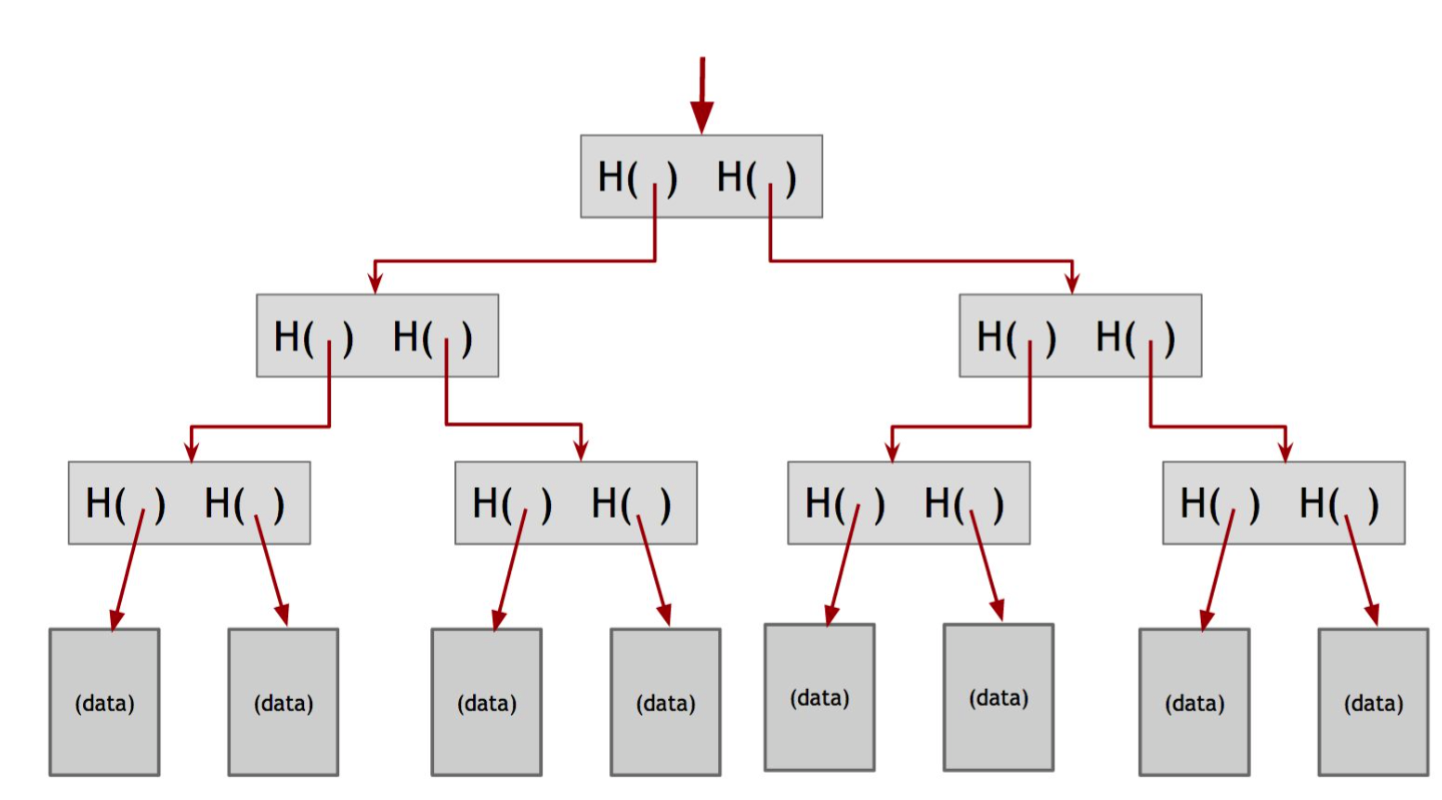

2.2.2 Merkle trees

Another useful data structure that we can build using hash pointers is a binary tree. A binary tree with hash pointers is known as a Merkle tree, after its inventor Ralph Merkle. Suppose we have a number of blocks containing data. These blocks comprise the leaves of our tree. We group these data blocks into pairs of two, and then for each pair, we build a data structure that has two hash pointers, one to each of these blocks. These data structures make the next level up of the tree. We in turn group these into groups of two, and for each pair, create a new data structure that contains the hash of each. We continue doing this until we reach a single block, the root of the tree. For example, suppose we have three data blocks, a, b, c. We can generate a merkle tree by doing the following steps:

d1 = dhash(a)

d2 = dhash(b)

d3 = dhash(c)

d4 = dhash(c) #since we have odd number of blocks, we append it with another c

d5 = dhash(d1 ‖ d2)

d6 = dhash(d3 ‖ d4)

d7 = dhash(d5 ‖ d6)

Here is graphical example of merkle tree with 8 data blocks.

Based on the structure of merkle, it can check the membership of data in O(logn) time and O(logn) space. Here is a nice post from Quora illustrating why.

3. Signatures

A digital signature is supposed to be the digital analog to a handwritten signature on paper. We desire two properties from digital signatures that correspond well to the handwritten signature analogy. Firstly, only you can make your signature, but anyone who sees it can verify that it’s valid. Secondly, we want the signature to be tied to a particular document so that the signature cannot be used to indicate your agreement or endorsement of a different document. For handwritten signatures, this latter property is analogous to assuring that somebody can’t take your signature and snip it off one document and glue it onto the bottom of another one.

In practice, the signature is usually implemented as private-public key encryption. The popular algorithm is RSA. A digital signature scheme consists of the following three algorithms:

- (sk, pk) := generateKeys(keysize) The generateKeys method takes a key size and generates a key pair. The secret key sk is kept privately and used to sign messages. pk is the public verification key that you give to everybody. Anyone with this key can verify your signature.

- sig := sign(sk, message) The sign method takes a message, msg, and a secret key, sk, as input and outputs a signature for the msg under sk.

- isValid := verify(pk, message, sig) The verify method takes a message, a signature, and a public key as input. It returns a boolean value, isValid, that will be true if sig is a valid signature for message under public key pk, and false otherwise.

We require that the following two properties hold:

-

Valid signatures must verify: verify(pk, message, sign(sk, message))== true

-

Signatures are existentially unforgeable

With signature, the receiver of the message can verify the validity.

4. Final remarks

Given the building blocks of blockchain and bitcoin, in next post, we will introduce the consensus and decentralisation schemes of blockchain and other more advanced features.